College Park Scholars has been coordinating an annual theme for each of the past few years. It’s a chance for students across our community to come together to engage in a shared intellectual experience. Whether it’s trash—our theme from the 2015–2016 academic year—power or something else, we take on a complex, multifaceted problem, work to understand its causes and impacts, and discuss how we might address it with thoughtfulness and creativity. The annual theme and related programming afford us the opportunity to realize on a grand scale an idea that shapes everything we do in Scholars: We learn better when we learn together.

Our 2017–2018 theme was “Going Viral: The Spread of Illness, Imagery, and Information in the Modern World.” As with our previous themes, we hosted a variety of events aimed at creating interdisciplinary conversation and intellectual community across Scholars programs. Here is just some of what we learned from this theme this year.

1. You know that one person who never seems to get sick while mysteriously everyone around them does? They’re not actually a super villain—just an “asymptomatic super spreader.”

Dr. Don Milton and the researchers behind the CATCH the Virus Study (“CATCH” stands for “Characterizing And Tracking College Health”) are dedicated to figuring out what makes people contagious—particularly in residence halls. This includes “asymptomatic super spreaders” who rarely display symptoms themselves but have the potential to infect those around them. Scholars students had the opportunity to participate, as both research assistants and study subjects, and the study gained significant media attention during this past flu season. The CATCH study will be continuing next year here in the Cambridge Community.

2. Zombie movies aren’t just scary stories; directors have historically used them as allegories about fears around greed or to “stand in” for other kinds of diseases.

The film “28 Days Later” (2002) has been described as revitalizing the zombie genre, which has become an incredibly lucrative one thanks to comic books–turned–television shows like “The Walking Dead” and the countless zombie movies that have been made in the last 16 years. But horror director George Romero created our “modern” zombie image back in the late 1960s with his “Night of the Living Dead” series, where themes of fear and hysteria around the unknown were brought (back) to life through staggering reanimated zombies. “28 Days Later” follows suit, with reviews remarking on its balance between traditional horror and political drama.

3. Self-care has gone viral in the last few years, becoming a lucrative multi-billion dollar industry.

Self-care apps, like Headspace and Calm, made $15 million in the first quarter of 2018 alone, and a quick Google search reveals countless companies capitalizing on an increased interest in mental, physical and emotional self-care. Though it began as a largely medical concept in the mid-20th century, the term has become considerably more complicated in the present day, with debates over what constitutes self-care regularly generating think pieces on a variety of websites. Regardless, groups like SPARC and events like our traditional finals-week “Puppy Pause” encourage Scholars to take time for themselves when things get most hectic.

4. Memes and image macros can both go viral, but they’re not the same thing—just ask Dr. Tom Holtz.

When Dr. Tom Holtz kicked off our “Memes and Other Mysteries” faculty panel in February, he offered a colorful history of the evolution of what we now call the Internet meme—including a few memes that featured him prominently. It turns out a crucial part of this evolution actually centered around the language we use to define the images we share on message boards, in texts and in other social media. One of the first sites that helped turn Internet memes into profit was “I Can Haz Cheeseburger,” a site that allowed users to put text over images to create image macros. Memes, however, have evolved since then—although an amusing photo of a cat with white block text remains iconic.

5. Businesses are strongly invested in the concept of virality, but need to remember to keep it authentic for success.

A number of students attending the “Memes and Other Mysteries” faculty panel observed that virality has to happen organically for it to feel truly natural and successful. Attempting to force something to go viral with the use of a hashtag or a YouTube influencer doesn’t resonate with college students in the ways that businesses might hope; the most successful businesses are able to evolve quickly to reach potential audiences. Nike, for example, has been financially successful with this strategy—even if some of their ads left students forgetting the company that created them!

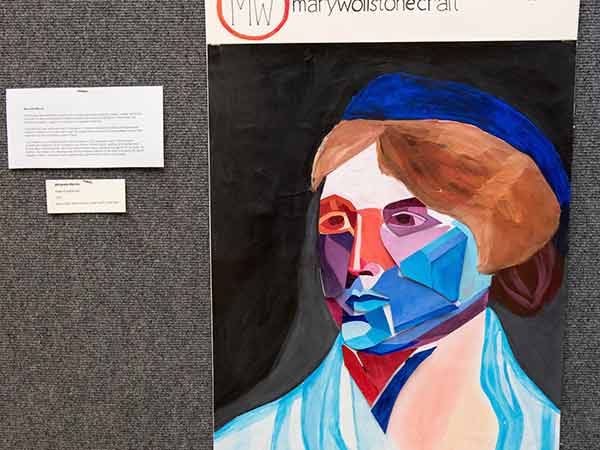

6. If historical figures had had Instagram, maybe some of their ideas would have spread even further. Or maybe they would have gotten a lot of online hate.

At ArtsFest this past April, Arts sophomore Miranda Morris imagined what 18th century feminist writer Mary Wollstonecraft might have shared on her Instagram, down to the “Instaenlightened” hashtag at the end of one of her most famous quotes on female beauty. In her artist’s statement, Morris wrote that she “chose to explore the infamous image-based platform’s effects on female self-image,” creating an abstract self portrait that looked much like the kinds of filters that pop up on social media. The piece examined the relationship between social media and reality, but also sparked questions about the ways in which these kinds of inspirational quotes are received in popular culture. In the end, it left viewers wondering just how many followers even such an influential figure might have had and what kinds of anonymous comments she might have faced.

7. The term “fake news” actually means much more than the definition that’s gained traction in popular culture.

Kate Starbird winced a bit as she mentioned the omnipresent term “fake news” near the beginning of her lecture, “Muddied Waters: Online Disinformation During Crisis Events,” in April. The term has come to have a distinctly political connotation, but it goes well beyond dismissing various news platforms. In reality, it can refer to clickbait, political propaganda, stories adjusted to manipulate readers and the media, or even “deep fakes”—images that have been doctored or spread with false captions, like the shark on the highway during a hurricane or the Parkland students ripping up the Constitution. The further challenge, Starbird noted, is that corrective information doesn’t work: Even once we’ve received correct information about the doctored image, our brain has already been impacted by the fake.

8. It’s just as important to pay attention to the way viral stories make you feel as how they affect you logically, because disinformation targets emotions.

Many of the strategies around assessing information we receive online, whether through a news story or a shared Facebook post, center on the idea of fact-checking and logic. Students are told to find the original source of a story, to check a website like Snopes or to consider where the information is coming from. In her April lecture to College Park Scholars, however, Kate Starbird reminded the standing-room-only audience that these techniques are just the beginning. Disinformation is meant to confuse and create doubt, and in turn demotivate people. Thus, Starbird urged students to also tune in to the way images and stories are impacting them emotionally, to confront their own biases and to use their emotional responses to help motivate them.

9. Hashtags like #MeToo resonate in part because they help people feel they’re not alone, and the arts can be a powerful way to explore that.

When then-Scholars student (now alum) Maryam Ghaderi heard about the Me Too Monologues three years ago, she knew the event would resonate in College Park Scholars. For the event, students submit anonymous monologues about identity that are then performed by other students. But the monologues took on new resonance in this year’s performance with the rise of the #MeToo hashtag around sexual harassment and assault, together with the increasing conversation around mental health and college students. A night of monologues, film and letter reading in April culminated in a talkback with the performers, during which one audience member, Justice and Legal Thought sophomore Cydnee Jordan, said that the real power of these performances is the opportunity to see ourselves in stories and to realize what we have in common with one another. That, in turn, helps us to heal.

10. Citizen activism was a potent factor in forcing government action during the AIDS epidemic.

The group ACT UP, started in the 1980s, recognized a crucial issue with the state of education around AIDS: It was almost non-existent, and the government was doing little to help that fact. Furthermore, access to treatment—or even information about treatment—was at a premium. Concerned citizens banded together to protest; to demand access to information, drugs, and treatment; and to try to effect lasting change for those who were already running out of time. The 2015 documentary, “How to Survive a Plague,” interspersed interviews with current and surviving HIV activists, physicians and protest participants with footage from that era. Students who viewed the film said they had never before seen this coverage, making this screening and talkback with Scholars Executive Director Marilee Lindemann all the more impactful to end our year.

11. Going viral can be a transformative experience—even if we can’t predict exactly where and how it will happen.

Whether it’s the nearly universal glee of dancing to “Gangnam Style” at a wedding (and the videos that flood YouTube documenting that very phenomenon), hashtags helping to get victims of Hurricane Harvey rescued in Houston or something in between, things that go viral help bring people together, to learn from one another and to share with one another. Next year, we’ll push this concept of connection even further with our 2018–2019 annual theme, “Migrations: Populations and Practices on the Move.”