“You’re going to Meredith Farm after this?” asked our tour guide, Matt Meredith, as I stood in the cramped interior of the Bucktown Village Store with 16 first- and second-year Scholars.

“It’s on the Byway list,” I explained.

“That was my family’s farm. There’s nothing there anymore,” Matt said.

Planning a trip along the Harriet Tubman Byway—the first centrally organized field trip for College Park Scholars as part of our annual theme, “Migrations”—was not just a question of logistical challenges, as I might have expected when we began planning this trip in the summer. At the time, I had assumed my primary concerns would be bus rentals, sign-ups, deposits and schedules. Instead, I faced challenges that drew attention to a broader problem of the history of migration stories: What happens when the physical proof—the tangible history—is no longer preserved? When there’s nowhere for students to stop and take in the history, how do we ensure they can make meaning of the narratives they’re hearing?

Fortunately, when you bring together a group of Scholars, the opportunity to connect and collaborate can help students find meaning in even unexpected places.

Migration narratives

The Tubman Byway website encourages potential visitors to spend “a couple of hours or a couple of days exploring.” For this excursion, I was tasked with finding something in the middle: a one-day outing for a mix of students across our Scholars programs. The drive to the start of the byway, on Maryland’s Eastern Shore, would take approximately two hours (and then two hours back to campus at the end of the day). That left us with about five hours’ worth of exploration. This meant ensuring enough stops so students could try to make meaning of the history, but not so many that they’d be overwhelmed by information. By the time we boarded the bus for the byway on the morning of Oct. 20, I had crafted what I thought was a decent itinerary.

That itinerary shifted almost immediately when we had to make an unexpected first stop. The “address” for the Tubman Memorial Garden proved vague: It indicated a highway intersection, with no specification of where exactly its mural—described as a perfect group photo op—might be.

So we pulled into the Dorchester County Visitor Center, which promised “information and orientation for the journey.” This would hopefully get us a better map than what I had found online, and give students a chance to stretch their legs.

As I went to pick up the map, a student exclaimed, “We’re in Cambridge? I live in Cambridge Hall!”

The moment struck me as not only endearing, but also enlightening. Our students come from a variety of backgrounds and places, and the Maryland history that informs the naming of campus buildings is not necessarily common knowledge. The trip was primarily intended to serve as a reflection on the narratives of forced and liberatory migration in the life of Harriet Tubman. That remark, however, reminded me that this trip also provided value by simply giving students a chance to experience the history and geography of Maryland itself.

Indeed, though many of the students on the trip recalled having learned about Harriet Tubman and the Underground Railroad at some point, details of her eight-year role as the “conductor” of the Railroad felt less familiar. Students’ knowledge of the direct connection to Maryland history was less familiar still. When we did find the mural and paused for a group photo, the students looked at the mural’s marsh scene on and asked, “Why is this the background?”

I was able to explain that the Underground Railroad traversed many paths, and when it came to the Eastern Shore, those paths included marshlands. Our guide at the Bucktown Village Store, Matt, reminded our students that one of Tubman’s biggest advantages when she began leading slaves toward the north was her intimate knowledge of those marshlands. “Imagine if you didn’t know the area, didn’t know the land. You’d take a step out there and be up to your chest in mud,” Matt pointed out. “She had to know where it was safe, and she only knew that because she’d spent her life here.”

Tangible history

As for the village store, it is described as the site of Harriet Tubman’s first act of defiance. Matt handed students 2-lb. counterweights to pass around as he told a story of how Tubman was struck by just such a weight.

The store remains one of the few places from Tubman’s life that remains intact. Students had the opportunity to touch the counters Tubman herself would have used, experiencing that tangible history alongside the stories of her life. As Matt noted, no one could have predicted who Harriet Tubman would become.

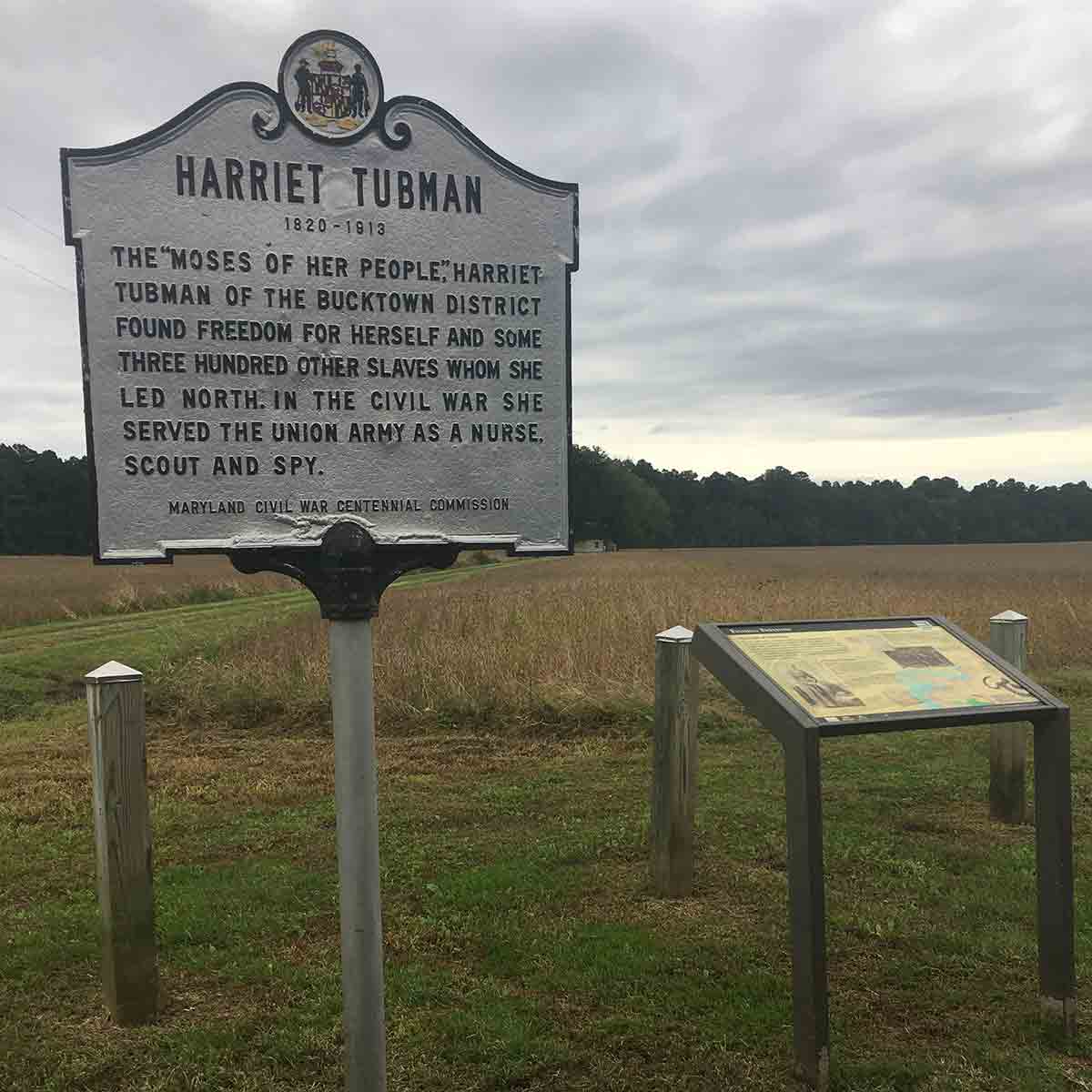

Even a visit to Tubman’s “childhood home”—the stop Matt suggested to replace our initial plan, the nonexistent farm—meant a visit to an empty field, with a single marker commemorating her life. By that point, we had already made a few stops along the byway. I was still concerned that students were having difficulty following the narrative. After all, on most tours, every important point features a voice-over or guidepost that tells you the story exactly as the museum or historians want you to remember it.

Would the students have enough context to make the connections themselves?

It would be at the next site, however, that the fullness of Tubman’s story would come to light for these students. The Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad Visitor Center opened in 2017. Operated by the Maryland Park Service in cooperation with the National Park Service, it offers visitors a powerful narrative of Tubman’s life, from birth into slavery, then to freedom. The entire center, our guide noted, is oriented toward the north, and the building itself is half-wood—representative of the physical labor Tubman did as a logger—and half–blue slate, designed to fade over time. (The latter serves as a visual representation of the ways in which the institution of slavery has faded out of our nation, but with a memory that still resonates.)

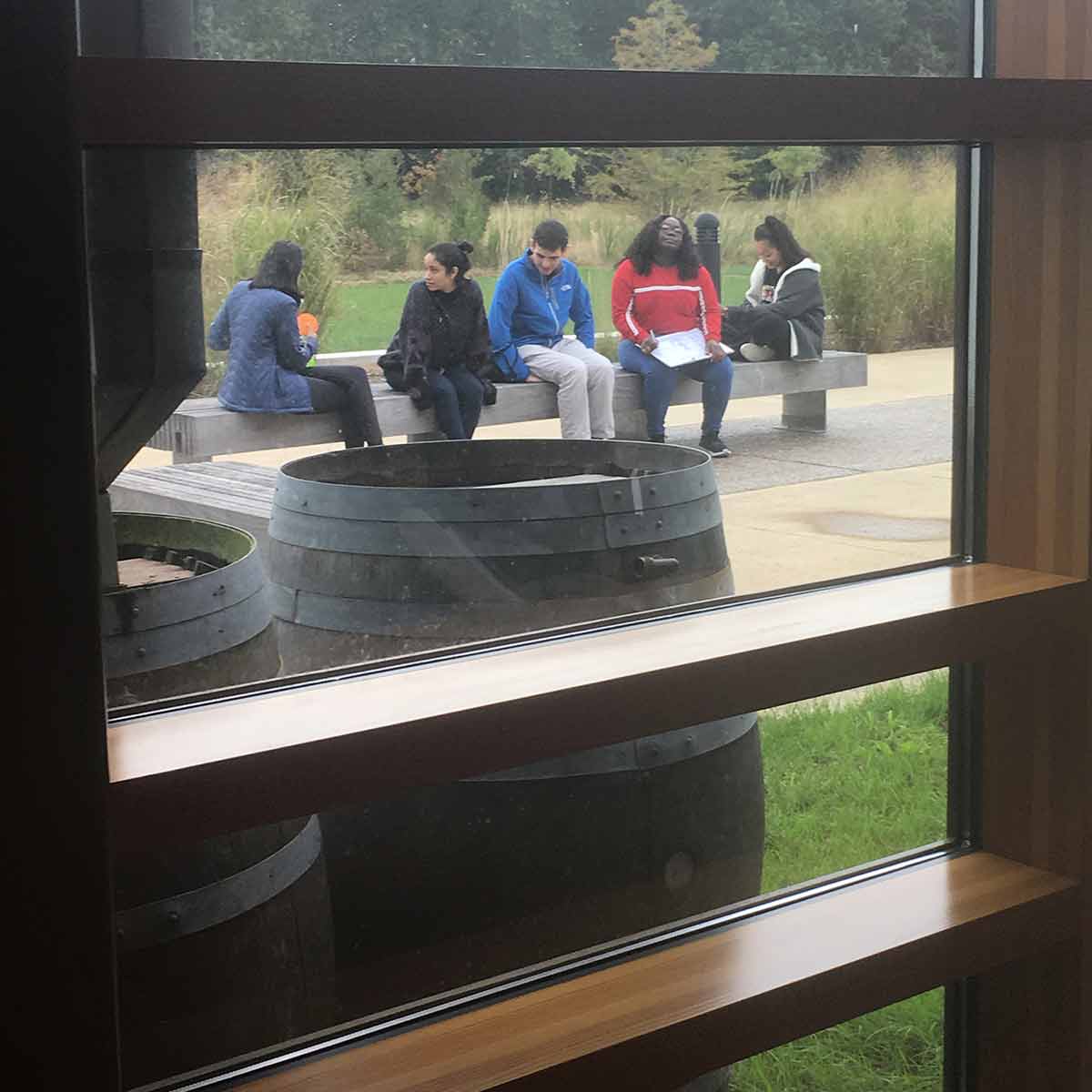

The path through the museum itself begins in a dark, cramped space. It moves outward to a wide-open space, with lights representing the night sky that Tubman would have followed to guide herself and her “passengers” to safety. The museum itself is not terribly big, but the students were in no hurry to move through. They walked slowly through the space, reading the signs, interacting with the exhibits and pausing to reflect on the ways in which her story moved beyond a single person.

Connecting to the story

When I walked up to the students—often in pairs or small groups—I asked if they were enjoying the additional guided activities they’d been handed upon walking in. I had assumed those guided activities would be the best way for them to feel connected to the intensely emotional story they were encountering here.

But I was pleasantly surprised to hear the students’ responses: They’d put those activities aside, because the prompts were interfering with the students’ ability to take the story in. The students wanted space to consider their own relationships to the information they were learning, and time to sit in the dark room with the starlit ceiling and listen to the stories of the lives Tubman had saved. The challenging concepts didn’t need to be explicitly explained. Instead, our students were choosing their own path, talking to one another, taking pictures together and sharing the common experience of learning outside of their comfort zone.

When we got onto the bus to head back to campus, the students looked at me expectantly. I suddenly realized that I knew exactly what to say to them.

“The point of this trip was to tell the story of migration, yes—to let you all think about the ways in which stories of migration can vary hugely, forced or liberatory,” I said. “But, actually, it was about more than that. It was about reminding all of us, including me, that this isn’t a history that’s in the distant past or located far away. I didn’t know that all of this was here. Neither did most of you. But now you do, and you have the chance to come back here. How many of you think you’ll come back sometime?”

Every hand went up.